What Constitutes Our Union?

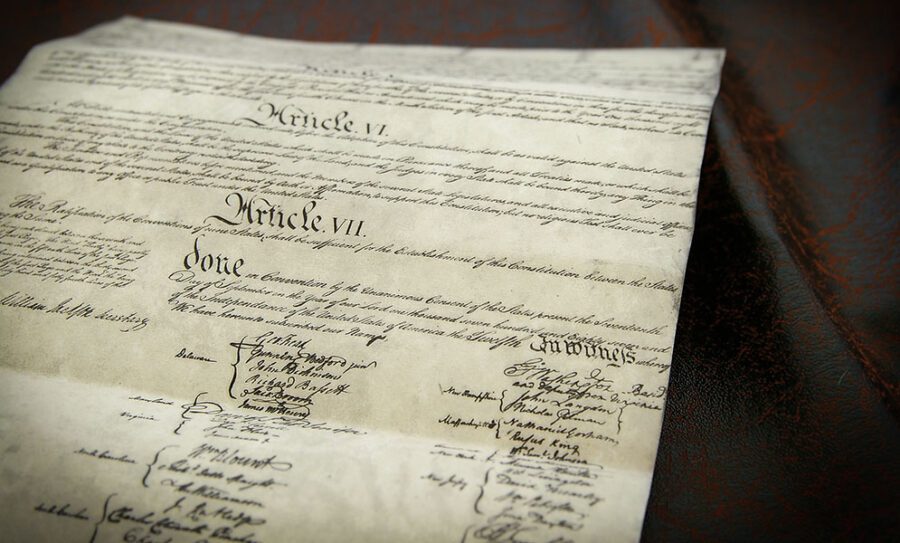

Constitution Day arrives each September 17th, calling us to reflect not just on a historical document, but on what truly constitutes our Union. The day invites us beyond the usual patriotic platitudes to engage with deeper questions about governance, liberty, and our civic responsibilities.

The Rules That Make the Game Possible

A friend noted that “the Constitution itself is extremely boring, in the same way that any rule book to any game is boring. But it is what makes the game itself possible.” This captures what makes constitutional reflection exciting. The Constitution isn’t thrilling for its prose—it’s remarkable for what it attempts: applying natural law to human governance.

Like retracing a family tree, we can see the descendants of timeless principles in our constitutional structure. Universal truths about human nature, justice, and the proper limits of government take concrete form in our governmental structure.

- The separation of powers reflects the principle that power corrupts.

- Federalism acknowledges that governance works best when it remains close to the governed.

- The Bill of Rights recognizes that certain liberties exist prior to and beyond government reach.

Beyond “What Would the Founders Say?”

This is where Constitution Day becomes more than historical remembrance—it becomes an active exercise in citizenship. Too often, we try to settle complex constitutional questions by asking “What would the Founders say?” This cliché question reveals some lack of historical awareness about the great divisive debates that churned through our infant nation. While the U.S. Constitution stands as a remarkable achievement, it is not infallible, nor was it unanimous in its interpretation even among its creators. Still, it serves as the recipe of the world’s most enduring constitutional republic.

The Founders themselves disagreed on key interpretations from the very beginning. Madison and Hamilton, both architects of the Constitution, famously split over the scope of federal power in the General Welfare Clause debate of the 1790s. This single debate opened the door to massive government expansion and bureaucracy, allowing the federal government to venture far beyond its enumerated powers into areas like education.

What the Founding Generation did have was a shared loyalty to principles, and they argued for the best means of protecting those principles.

The Founders’ Shared Method

What else did the Founders actually share? While there wasn’t unanimous agreement on every constitutional question, there was a common approach to constitutional reasoning. They started with basic principles:

- power corrupts,

- governments exist to secure rights,

- authority should be limited and divided, and

- and other time-tested observations.

They examined structure and purpose, considered consequences for liberty and civility, and engaged in vigorous principled debate.

Even when Hamilton and Madison reached different conclusions about the scope of the national government, both used constitutional reasoning. They reasoned from principles about what would best protect liberty and restrain dangerous concentrations of power.

Our Inherited Obligation

This is the method we inherited: disciplined reasoning from constitutional principles, not ancestor worship. The Founders valued this process of constitutional reasoning precisely because they knew future generations would face circumstances they could not anticipate. They gave us principles and a method for applying them, trusting that we would do the hard work of constitutional thinking rather than simply looking backward for easy answers.

Our obligation isn’t to mimic the Founders’ specific conclusions, but to continue their principled argumentation. We must engage in the same kind of rigorous reasoning from constitutional principles that they modeled, even when—especially when—it leads us into uncharted territory.

Educational Independence as Constitutional Application

Let’s apply this constitutional reasoning to a concrete example: education. Here we find remarkably clear constitutional ground. Education appears nowhere in the Constitution’s enumerated powers. The 10th Amendment makes this crystal clear: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

This isn’t a conservative versus liberal issue; it’s a constitutional structure. Even Hamilton’s broad interpretation of federal power in the General Welfare Clause debate didn’t extend to direct management of education.

Applying Constitutional Principles to Education

When we apply constitutional reasoning to education, several principles point toward local control and educational independence.

Limited Government and Federalism work together to keep educational authority as close to the people as possible. The most local level of government is the family, and securing the rights of parents to govern their children’s education represents the truest form of local control. This isn’t just administrative efficiency—it’s a fundamental check on the concentration of power at any distant level of government.

Democratic Accountability flourishes when citizens are educated and virtuous. Education independence creates the conditions for this kind of citizenship by allowing families to pursue education according to their values and circumstances, outside the governance and control of power structures that are historically proven to corrupt.

Individual Liberty finds expression in education independence through the protection of parental rights and family autonomy. God has made parents, not distant bureaucrats, responsible for providing for their children’s needs and exercising their family’s values. Parents also know and understand their own unique circumstances.

The Restraining Function

Education independence serves the Constitution’s restraining function by limiting federal overreach and preventing dangerous concentrations of authority. When educational decisions flow from Washington, D.C., they inevitably reflect the values and priorities of whoever holds federal power rather than the values of individual families.

Good Citizenship in Action

This brings us back to our civic obligation. Good citizenship in education means engaging actively in local governance, supporting constitutional boundaries, and doing the hard work of local decision-making rather than defaulting to federal solutions.

Education independence isn’t just a policy preference—it’s constitutional reasoning applied faithfully to one of the most important elements of civil society.

Constitutional reasoning isn’t a one-time exercise but an ongoing civic responsibility. Each generation must apply constitutional principles faithfully to their own circumstances, doing the hard work of principled governance rather than simply looking backward for easy answers.

The Foundation of Liberty

Thomas Jefferson understood that this work requires a certain kind of citizenry. He wrote:

“Educate and inform the whole mass of the people, enable them to see that it is their interest to preserve peace and order, and they will preserve it, and it requires no very high degree of education to convince them of this. They are the only sure reliance for the preservation of our liberty.—After all, it is my principle that the will of the majority should prevail. If they approve the proposed constitution in all it’s parts, I shall concur in it chearfully, in hopes they will amend it whenever they shall find it works wrong. This reliance cannot deceive us, as long as we remain virtuous…”<link>

Jefferson’s insight cuts to the heart of constitutional government: it depends not on perfect institutions but on virtuous citizens willing to do the work of self-educating and to wrestle with what you learn with those around you. The whole experiment in self-governance rises or falls on this question of virtue.

Our Generation’s Constitutional Task

The Founders’ true legacy isn’t their specific policy conclusions but their commitment to principled governance and constitutional reasoning. They gave us a method for restraining government and defending liberty that each generation must apply anew.

In education, as in other areas of governance, this means returning authority to its proper constitutional bounds.

Our generation’s task comes with a solemn reminder: every elected official swears an oath to uphold the Constitution. But oaths alone do not guard liberty. The mechanism of enforcement is the people themselves—their constituents. That means we must know the Constitution, attend carefully to the performance of our elected officials, and take seriously the duty to evaluate whether they are keeping their oaths. Holding oath-keepers accountable and removing oath-breakers through our votes is the essential work of constitutional self-government.

Constitution Day as Civic Renewal

Constitution Day should be more than a historical commemoration. It should be an annual reminder of our obligation to continue the work the Founders began: the never-ending task of restraining government power and defending human liberty through principled constitutional reasoning.

Will we do the work of virtuous citizenship that the founders entrusted to us? Will we continue to constitute the Union they envisioned, one generation at a time, one principled decision at a time?

That work begins with each of us, in our families, our communities, and our civic engagement. The Constitution made the game of self-governance possible. Now it’s our turn to play.

Taking Action: Engaging as a Citizen

- Know the Constitution– Learn its principles and structure.

- Observe and Evaluate Officials– Hold elected officials accountable to their oaths.

- Participate Locally– Attend meetings, vote thoughtfully, and support governance close to the people.

- Share and Discuss– Encourage others to understand and defend constitutional principles.